As new OMB Director Mick Mulvaney, in consultation with the Director of OPM, prepares a plan for reducing the federal civilian workforce, attention will focus on successful reform models.

Georgia’s civil service reforms are most the extensive of any state government reforms attempted in the past 30 years. They have been in place for more than 20 years, and two of Donald Trump’s cabinet-level appointments have extensive Georgia-related experience.

Tom Price is a current Georgia congressman and former state senator who is slated to head HHS, and George “Sonny” Perdue is a former two-time Georgia governor now nominated to serve as Secretary of Agriculture.

In 1996, Georgia took its civil service system and turned it upside-down. Employees hired after July 1, 1996, serve at will with no civil service protections and no seniority rights.

A five-member State Personnel Board appointed by the governor is responsible for setting statewide HR policies. The state’s centralized personnel system has been abolished, and agencies have responsibility for recruiting and selecting new workers, as well as for setting pay, job duties and promotions. Employees have limited rights to appeal.

Employment post-civil service

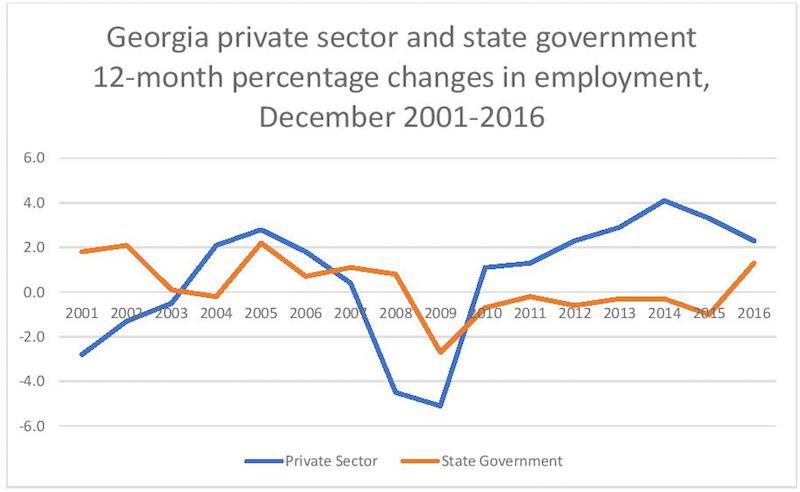

The impact of the elimination of most civil service protections in the state is most apparent when comparing state government employment following the most recent 2007-2009 recession.

Traditionally, government workers were less affected by economic cycles. In recessions, while private sector employment would fall, government employment would act as a stabilizer on the overall economy acting countercyclical to the private sector.

For example, nationwide private sector employment fell by 8.5 million between January 2008 and January 2010, federal employment rose by 132,000.

In Georgia, private sector employment dropped by almost 10 percent over that same time period, but instead of acting as a stabilizer, without civil service protections state government contributed to the downturn through a combination of not filling vacant positions and layoffs.

State government employment fell nearly 3 percent between 2008 and 2010, and then continue to fall. By July 2015, Georgia state government had shed a total of 9 percent of its jobs, and is only now recovering as the state economy rebounds.

Without traditional protections, Georgia’s state employees became a procyclical drag on the state’s economy as layoffs in the private sector were extended into state government as well.

Minimal Impact on Wages

While employment declined, those state workers keeping their jobs saw their pay keep pace with the private sector counterparts and their fellow state employees in other states.

From 2007 to 2015, average weekly wages in Georgia’s private sector grew by 17.7 percent, while the average weekly wage of a Georgia state employee rose by 21.7 percent, about the same as for state employees nationwide.

Before the recession, average pay for Georgia state employees was roughly 14 percent below the average paid by private employers in the state, and that relationship was unchanged by the economic downturn.

Georgia state government employees have gone several years without pay raises, but states with greater civil service protections also delayed increases, so the loss of protections did not affect wages as much as employment.

Fears of Political Patronage May Be Exaggerated

Civil service reform always raises the specter of greater political patronage affecting the hiring and promotion process in government.

Since 1996, Georgia has been led by two Democratic followed by two Republican governors, but by most accounts, political patronage has not increased in Georgia despite the lack of civil service protections.

While state government tends to be more political than the federal bureaucracy, changes in the governor’s office has not led to greater politicization of state employment.

Despite the change in parties, the state remained politically conservative throughout this period. Whether there would be a wholesale discharge of state employees if the state’s governor suddenly swung from politically conservative to liberal is impossible to predict.

With its 20-year history of radical reform, Georgia’s attempts to create a more responsive, less centralized state bureaucracy may become a model for President Trump’s plans for the federal government.