Anyone who reads this column and the comments thereto knows that the art of whinemaking is alive and well in the Federal service. Having spent an inside the Feds career and an outside but advising/training post career helping managers resolve employee problems, I stopped being surprised long ago by the nature, frequency, origin and initiators of the various whines served up to supervisors.

Like the grape, there are a great variety of whine types, vintage whines, and whineries but few really fine whines. Also, like the grape, whines are cultivated everywhere and advanced by their purveyors as the best in existence.

Is He Kidding?

By now you are asking, “Is this a serious article?” The answer: you bet. Ask any supervisor or manager what are the top 5 most difficult tasks they face in their jobs and most will place listening to and resolving employee complaints at or near the top of their short list. I get asked about it in class all the time. As a result, I’ve developed a suggested range of approaches managers may employ when faced with whinemakers.

Whinemaking is not a Specific Symptom but a Generalized Condition

Before we get to the list of to dos, there are some matters that must be understood. First, people with whines to sell aren’t always people with problem conduct or behavior. Some very productive people whine all the time. Also important to recognize is that some employees who have or create big problems for management never whine at all. As a result, I’ve come to believe that whinemaking is nurture not nature. There are some with a great justification to whine but never do so and others (reaching virtual constancy in their whines) who, based on their attitude or performance, ought to be thankful for any employment, doing anything at any pay for any organization and just shut up.

Getting It vs. Not Getting It

Getting it is an Agency, organization, or work unit specific thing. Getting it is often the opposite of whinemaking. Explaining things to someone who gets it is redundant. On some issues, the Borg win and “resistance is futile.” On others, a well considered word or two may prevail while an endless diatribe does little. Picking your issues is, of course, an art not a science but can be practiced to competence. If you spend time with a group of people, it can become obvious pretty quickly who gets it and who doesn’t. I believe that a failure to set clear expectations for both performance and conduct contributes mightily to whether a group or the individuals who make one up get it or not. More about this later.

The Bliss of Being a Coworker and Not a Supervisor

Unlike supervisors or managers, employees have great freedom to address the whinemakers with whom they work. I remember clearly a coworker of mine, a usually very quietly competent person, who at a staff meeting had clearly had enough. Addressing the whinemaker (thankfully not me at the time) said, “Enough is enough, I don’t know about everyone else but I’ve had it with your carping and complaining about everything. I believe you come to work to complain because no one will listen to it at home anymore.” This lady said so few extraneous things that the whinemaker actually stopped (for about a week). I remember another frazzled coworker who, having heard enough from the same whinemaker in a meeting with another organization told the visitors “Don’t pay attention to him, we don’t”.

Supervisors and managers must exercise more discretion than this. In this era, little tolerance exists in higher echelons for supervisors whose frankness exceeds certain organizational behavioral norms. That’s a nicer way to say what I mean, get it?

So What’s to Do?

Supervisors and managers have, or more importantly believe they have, the duty to listen to the “concerns” of each employee and seek to resolve each and every one. That’s silly of course, but very, very widely believed. One cannot compete successfully with such an article of faith, so my response is “OK, what are we going to do about it?”

When the Best People Whine

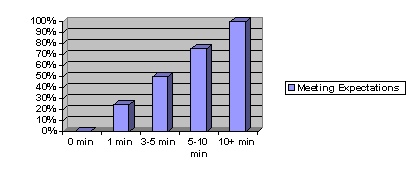

The approach, like all good principles of management, should be situational not fixed. What a manager does should be guided by a rule that’s relevant to the person and the environment. A beginning rule of thumb is reflected by the chart below. The attention we give to whinemaking should be in direct proportion to the value of the whinemaker. I’m not suggesting encouragement of whinemaking but recognizing the absolute reality that those who are the most productive, not the least, are worth a fair amount of listening time, usually without much comment.

Frequently whinemakers of this productivity don’t really want anything but an ear. Give it to them. Be careful it doesn’t become a daily or even, perhaps, weekly thing but hear them out, thank them for coming and then get them back to work. As you go down the productivity ladder, a very different approach is warranted.

Low Producing Whinemakers

Patience and forbearance with marginal producers is not a virtue. One of my clients, a Naval Activity, had an interesting slogan on the wall in its entrance hall. “We’re not interested in lengthy reasons why a necessary thing cannot be done”. The IBM commercial says it all. “STOP TALKING, START DOING!”

Your Obligation to the Lower Producing Whinemaker

When faced with a whinemaker on the declining scale of the chart, here are some approaches to consider.

- Listen long enough to get the issue. Either address it then if you have sufficient information to respond or thank them, send them back to work and take whatever time necessary to formulate an appropriate response but don’t get caught up in a lengthy complaining session.

- Treat people with respect and dignity, of course, but don’t let a subordinate drive your agenda unless their idea is better than yours. A rare circumstance among the low work but high whine producing staffer.

- If an answer is warranted, find it out and give it to them. Even whinemakers may have a legitimate issue. Screen for that and react appropriately.

- Refer issues not your own. If the whine is about something outside your control e.g., an HR, travel, pay, benefit or other institutional rule or issue, offer after due consideration to take the matter up with the appropriate office if the whine appears worthy. If they got an answer and either didn’t like it, didn’t agree with it or have other complaints, direct them to the appropriate appeal system. There always is one. But whatever you do, be very careful of involving yourself in another office’s area of expertise without substantial cause.

- Be wary of those seeking “justice.” Also a possible quagmire is an employee’s quixotic pursuit of what they believe they deserve. Stand behind someone who has a legitimate issue but use care in assuming the merit of a longstanding (vintage) whine.

- Never, Never Whine to Your Staff! If you have an issue with your supervision, take it there. Supervisors and managers who complain to their staffs about their problems are inviting everyone under their supervision to become a whinemaker and not to them but to the next level of supervision. Once, like Pandora, that box gets opened, it is most difficult, if even possible to get shut again.

- Take control of the discussion and focus on performance expectations, if that’s the issue, or conduct, if that’s what’s driving the conversation.

- Drive the discussion into very specific outcomes. Most meetings with skilled whinemakers are about the practice of whinemaking not organizational results. My first articles with FedSmith were about the “best tool in the toolbox.” Use the discussion to start work on addressing the problems of the low producer.

- Refocus people on work whenever possible. Keep a list of your concerns about an individual’s work and what they can do to improve it when they come knocking on your door.

- Never take anything personally. Whinemaking is about them not you. Act only on a business basis. Taking notes when dealing with a seasoned whinemaker is a good idea. The best way to work the process is “Here’s what I heard, here’s what I did about it”.

None of this is fun. All of it is work and why you get those big bucks for supervision (Don’t we wish?). It’s about having goals, consistently and effectively communicating them and working through getting them accomplished.

Any opinion expressed above is mine and mine alone. Please keep those comments coming in. They help keep me honest. Honestly!