One of the themes I have written about over the years is the idea that the federal workforce is too varied and diverse to try to make one-size-fits-all programs for the entire workforce. It is a principal reason that measures like OPM’s 80-day hiring model don’t work.

When we look at the differences between agencies or occupations or geographic locations, we find that the experience of one group of federal workers may bear little resemblance to that of another group.

Those of us who have worked in the DC area and in the field can attest to the profound differences between being a federal employee in DC and being a federal employee in Florida, or Ohio, or California, or just about anywhere else.

Some of that difference is the headquarters v. field divide. I have heard both headquarters and field folks complaining about the other, saying they have no idea how things really are.

Field folks tend to think headquarters people just get in the way, while headquarters people think field folks have no understanding of how policy making works, what it is like to deal with Congress, or even with the senior officials in their own agency.

All of those are partly true, wrapping biases and misperceptions in a kernel of truth. But they are such sweeping statements that they don’t hold up under closer examination.

Types of Jobs

One area where there is significant difference is the type of jobs we see. In DC, the grade levels are much higher, leading to higher pay.

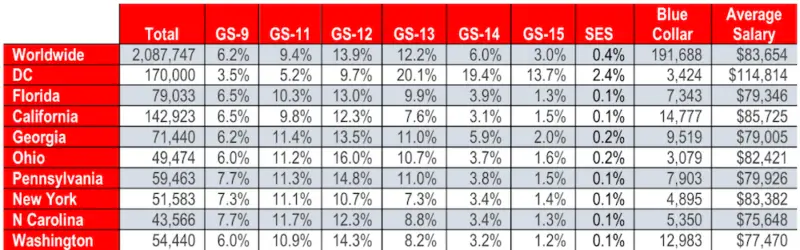

As you can see in the following table, the average pay of feds in DC* is more than $31,000 higher than the overall federal workforce. It is more than $35,000 higher than feds in Florida and Georgia, and more than $39,000 than those in North Carolina.

There is an obvious explanation why that is so – Washington, DC is the seat of government and OPM classification standards give greater credit to headquarters jobs that drive agency policy.

That does not explain why non-headquarters jobs in the DC area tend to be one or two grade levels higher than their counterparts in the field. Competition for scarce talent is the most likely cause of that discrepancy.

Another difference is the percentage of trade and craft jobs outside of DC. Roughly 10 percent of federal jobs are blue collar, while only 2 percent in DC are. Those jobs tend to pay less than general schedule and other white collar jobs series.

Supervisory Ratios

Another difference is in supervisory ratios. Even though grade levels are much higher in DC than in the rest of the country, the number of supervisors per employee is almost twice the number in Ohio, Georgia, or any other state.

The difference is partly caused by the type of work in the field. We typically see more jobs that are done in larger teams. In DC, we see smaller work units that are more specialized.

| Locality | Supervisory Ratio |

|---|---|

| DC | 1:5.3 |

| Florida | 1:9.0 |

| California | 1:10.8 |

| Georgia | 1:9.6 |

| Ohio | 1:9.5 |

| Pennsylvania | 1:9.3 |

| New York | 1:9.6 |

| North Carolina | 1:10.1 |

| Washington | 1:8.0 |

The fact that there are good reasons for the differences in grade levels, types of work, pay and the number of supervisors does not make the effect of those differences any less important. Being in an organization where 55 percent of the employees are GS-13, 14, 15 or SES is much different from one where only 12 percentare at those levels. The same applies when you work in a town where the majority of the total workforce are either federal employees or federal contractors.

I spent 10 years working in Jacksonville, Florida. The Navy was the biggest employer in town, due to having 3 Navy bases. Even so, most people were not involved with the Navy or the federal government. That difference changes the mindset of the federal workers, because the town did not live and breathe government.

Another big difference in field locations is the expectation of promotions. In the DC area, getting promoted to GS-13, 14 or 15 is far easier, because half the jobs are at those grades. In the field, where only 1 in 10 jobs are GS-13s and only 1 or 2 in 100 are GS-15s, the expectation of where a career might top out is different. Getting to GS-13 is a big deal.

Other Differences

There are some other big differences.

In the field it is uncommon to find anyone who has testified before Congress, or who has worked with the agency head and most senior officials. In DC that is not such a big deal.

When we talk about the federal workforce, all of these differences are important. What might be important for the GS-9 in the field may be of no interest to the DC federal worker, and vice versa. That isn’t bad, it is just reality.

Those who try to lump all federal workers into one big pot are doing a disservice to federal workers and are probably not doing themselves any favors either. The politician who fed bashes because s/he is taking potshots at the GS-15s and SESers in DC is also talking about the GS-11 in the field who does not get involved in policy and other DC-oriented tasks.

We would all be better off if we recognize the differences and the similarities between DC and field employees. I’m not optimistic that we will see that any time soon.

* Data for the entire national capital region is much harder to come by, so this information includes the District of Columbia only. Because a significant number of federal employees in the NCR are in Maryland and Northern Virginia, state level totals for those states are not included.