In September of 2019, the TSP rolled out their much-anticipated new withdrawal rules which finally brought thousands of retired TSP participants relief from the previous stringent withdrawal restrictions.

Unfortunately, the recent Coronavirus and subsequent sudden market downturn has exacerbated the single biggest problem with the new rules. The simple fact that retirees actively withdrawing funds for retirement income cannot pick which funds their actual withdrawals originate from is a major flaw. Put simply, if your TSP account is divided into 50% G-Fund and 50% C-Fund, every dollar you withdraw must come out in the exact proportion of 50% G and 50% C.

Financial advisors and I say the #1 rule of retirement distribution planning is to schedule your withdrawals to come from the investments with the least volatility. Simply put, you don’t want to take money out of a declining investment. We call this phenomenon the Sequence of Returns risk.

In my example above, because the market has gone down about 30% in the last month, and if you were taking a monthly withdrawal, you would need to withdraw 30% more from the C Fund to keep the same level of income. On the surface, that is no big deal, but it actually is a HUGE deal.

When you withdraw money from an investment you are actually ‘selling shares.’ When that investment suddenly declines in value and you still need your same annual income, you need to sell MORE shares to accomplish this task than you did the time before it fell in value.

Why is this so damaging? Should it even matter because the fund will eventually go back up?

Unfortunately, it matters a great deal. When the investment you withdrew from eventually recovers, you own LESS shares than you did before and you also have LESS shares in which to compound upon. If this happens a few times in the first 10 years of retirement, it could exponentially cut years from your retirement.

Case Study

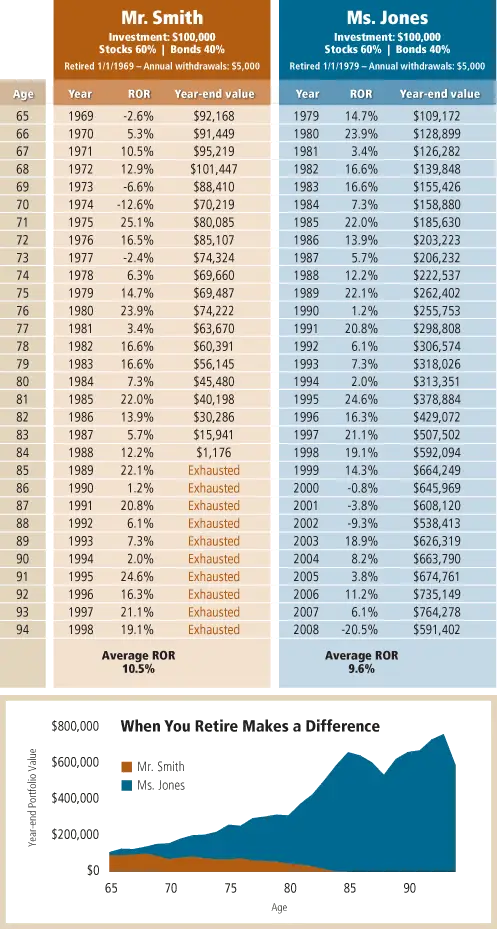

Let’s see this in action by comparing two Federal retirees, Mr. Smith and Ms. Jones.

Mr. Smith and Ms. Jones retired with the same amount of money, $100,000. The only difference is that Mr. Smith retires 10 years before Ms. Jones.

Both invested in a mix of stocks and bonds, taking 5% per year initially, then increasing the percentage withdrawn each year to keep up with inflation. The 10-year difference in their dates of retirement had a significant impact.

Mr. Smith experienced negative returns in four of the first ten years as well as elevated inflation rates. Although his rate of return was higher, the combination of lower returns and high inflation caused the inflation adjusted exhaustion of his portfolio after just 15 years.

Ms. Jones, on the other hand, experienced negative returns in only two of the first ten years in retirement. Although she also experienced periods of higher inflation, timely positive market performance helped to grow her assets in the early years, and a strong bull market helped the assets continue to grow as she took income from the portfolio.

The main difference between these two retirement scenarios was that Mr. Smith had the misfortune to retire at the wrong time.

*Data based on two 31-year periods ending on December 31, 1998 and 2008, respectively. Each portfolio assumes a first-year 5% withdrawal that was subsequently adjusted for actual inflation. Each portfolio also assumes a 60% stock/40% bond allocation, rebalanced annually. Stocks are represented by the S&P 500. The Standard & Poor’s 500 Index (S&P 500) is an unmanaged group of large company stocks. It is not possible to invest directly in an index. Bonds are represented by the annualized yields of long-term Treasuries (10+ years maturity). Inflation is represented by changes to the historical CPI. Past performance does not guarantee future results. This illustration does not account for any taxes or fees.

How can we fix this?

One simple solution is to invest less aggressively. Most people understand it is common wisdom to reduce risk in a portfolio during retirement in order to lessen worry about market losses. Heck, just invest in the G Fund, or better yet, the L-Income Fund.

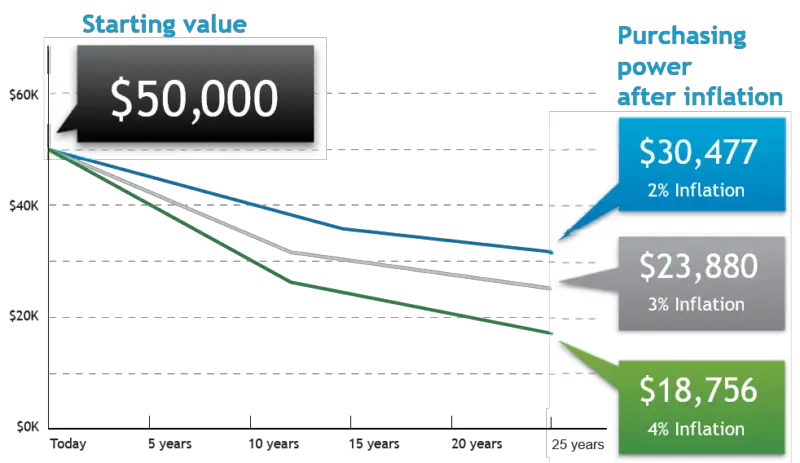

Investing ‘safely’ might fix the issue with market risk, but it then exposes you to a problem just as big: inflation.

Over time, the erosion of purchasing power caused by inflation can be just as devastating to a portfolio. If you invest too conservatively, you will run out of money, albeit a little later in life. The chart below illustrates how inflation has a dramatic effect over time.

The Federal Retirees’ Dilemma

If combating inflation is the problem, I should invest for more growth. Right? But if I invest for more growth, I might get “unlucky” and expose myself to market risk. (#coronavirus2020)

Neither of these scenarios sound like a good idea either. What’s the solution?

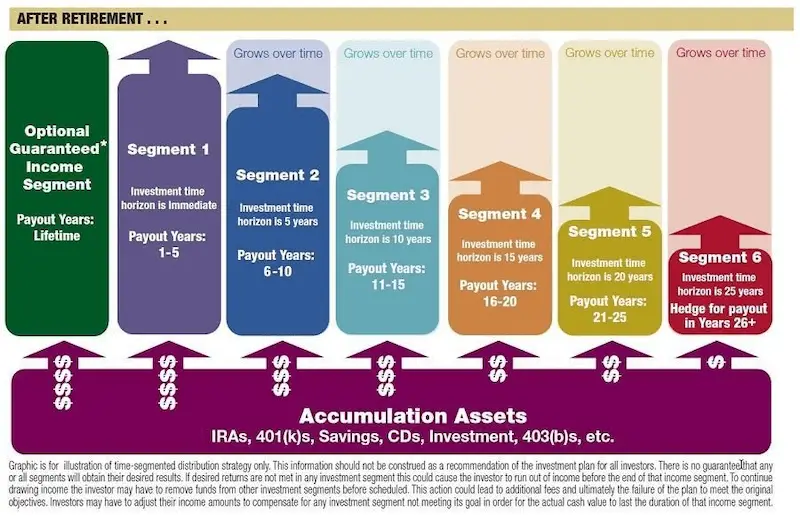

The Answer: Time Segmented Investment Strategy

Rather than “go for broke” or “play it safe,” just do both! But do it with purpose.

It’s important to segment your portfolios, assign a very specific investment strategy to them and then spend the money out of their assigned accounts when the time is ready.

Conservative accounts do the heavy lifting early on in retirement while the more aggressive accounts are allowed to grow (ups, downs and all) without the need to take money from them until much later. As the year goes on, you transfer money from more aggressive accounts into the safer accounts in pre-planned intervals that you control.

Graphically, it looks something like this.

But can you do this within the TSP? No, you can’t. And that’s our issue. The TSP did many great things with the new rules but inexplicably left this out.

After the dust settles and some of the current market volatility wears off, think about withdrawing some funds from your TSP, rolling them to an IRA and customizing your withdrawal strategy.

Yeah, I said that.

You might be saying, “Whoa—I didn’t think this was a sales pitch!” Rest assured it’s not. There are plenty of low cost, high quality investment vehicles out there that will allow you to customize your retirement distribution strategy to battle both sequence of returns risk and inflation risk. Many brokerage houses have gone to zero or near zero fees and no-commission transactions. Those are great options if you don’t want or need a financial advisor.

If you take anything away from this article it’s this: Don’t let blind faith in the TSP cause you to lose money because of a problem in their system. I hope that the recent market events will spur the TSP to take a fresh look at their distribution rules, but until they do, you should.

The opinions and forecasts expressed are those of the author, and may not actually come to pass. This information is subject to change at any time, based on market and other conditions and should not be construed as a recommendation of any specific security or investment plan. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Securities offered through Securities America, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. Advisory services offered through Securities America Advisors, Inc. Mission Point Planning Group and Securities America are separate companies.