As revealed and discussed in this article, the vast majority of discrimination complaints result in a finding for agency management.

While there a many reasons why complaints without merit are filed, in this article I have chosen to focus on the managers who must wait for judgement as to whether they have committed EEO offenses. While they are likely to be exonerated, the process itself may leave them scarred and less effective. If and when that happens, the impact of EEO allegations and complaints are far greater than the government is acknowledging.

For decades I’ve made my living presenting seminars to Federal supervisors, managers and union officials. During one titled Dealing with Performance and Conduct Issues, I take time to remind supervisors and managers that, when addressing personnel issues, they should not be surprised when an EEO complaint is filed against them in response to actions they take.

I also discuss the workplace hell experienced by those who have been discriminated against due to race, color, age, gender, national origin, disability and sexual identity/orientation. I have seen first-hand how disciplinary and performance-based actions can be weaponized for all the wrong reasons.

Who is this guy anyway?

While I’ve been earning a living teaching classes, when off-the-road I volunteer time as a mediator. These mediations include Federal EEO complaints and “pre-complaints”. The EEO process is complex, time consuming and expensive. Mediation (or ADR) is an early turn in a labyrinth outlined here: federal EEO complaint process. Having pioneered the practice in the 1990s, the Seattle Federal Executive Board provides no-cost mediation to agencies in the Northwest – the largest category being alleged discrimination.

Long ago, I was a Labor/Employee Relations Specialist who (among many other duties) represented Department of Navy supervisors and managers whose EEO cases went before an EEOC Administrative Judge. I have won, lost and settled. I have dealt with the innocent and the guilty…and I come from a family that has experienced some of the more virulent forms of workplace discrimination.

How many complaints have nothing to do with EEO?

Years ago, an EEOC Administrative Judge told me, “Four out of five Federal sector EEO complaints have nothing to do with EEO.” In other words, while there may be a complaint against management actions/treatment, it’s not based on race, color, age, gender, national origin, disability, religion, or sexual identity/orientation.

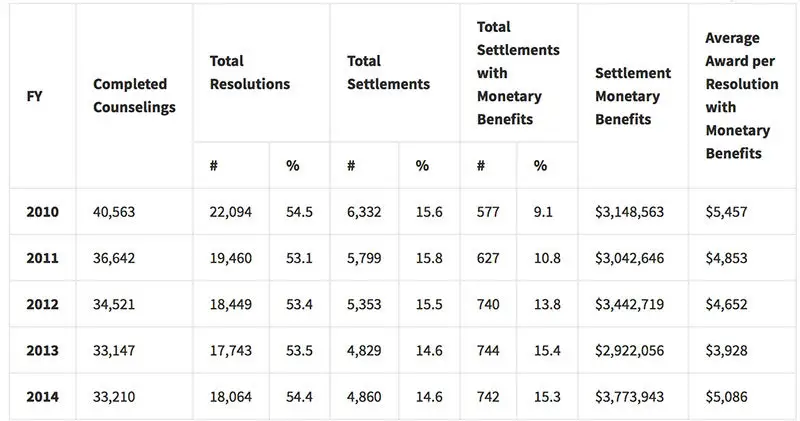

It appears as if statistics bear that out. The last year for which I can find the EEOC’s statistics in this regard is 2014. Thorough readers may want to read the whole report.

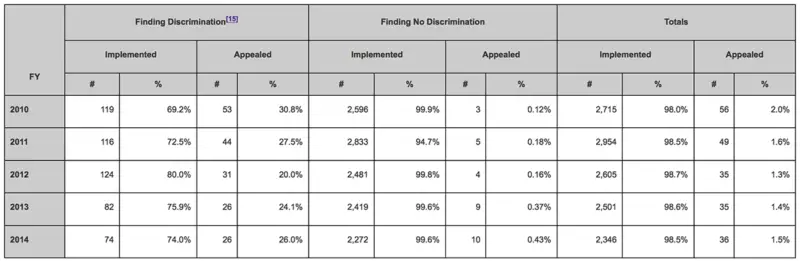

In Table 15 (shown below) the data show EEO allegations that “went formal” (resulted in a “complaint”), were then investigated, and from there went on to an EEOC hearing. There was a finding prohibited discrimination 100 times and no discrimination 2,282 times.

Table 15 – Agency Actions on Administrative Judge Decisions FY 2010 – FY 2014

Take a breath and look at the numbers above once again. They are remarkable.

As I read the data, the agency prevailed in EEOC hearings approximately 23 out of every 24 cases. Reports from previous years are consistent with 2014. I have been unable to locate more recent data on the EEOC’s website.

A deeper dive

Such overwhelming evidence that agencies will prevail when cases “go to hearing” bears serious scrutiny.

Anyone familiar with the EEO process knows that when cases look like losers, they are likely to be settled by agency representatives before they get to the hearing stage. The data from the EEOC that I’m citing doesn’t account for settlements and, therefore, may not reflect a bigger picture.

Settlements, however, also take place even when allegations of discrimination are considered to be without merit. Government attorneys take this tack in order to avoid the costs of investigations and hearings. Executives may see EEO complaints as a blemish on their records, thus encouraging the settlement of cases where no prohibited discrimination occurred. One gets a sense of this strategy when digging into the data.

At the “pre-complaint” stage, cases that settled with money exchanged, the average settlement amount came to $113 per completed counseling and $776 per recorded settlement as shown in Table 6 (below). That’s not much money. Moreover, a settlement rate of under 15% doesn’t seem very significant in light of agencies prevailing at hearing in over 95% of cases.

Table 6 – Monetary Benefits Awarded in Settlements During the Pre-Complaint Stage of the EEO Process FY 2010 – FY 2014

Tit for tat

What needs to be acknowledged is a secret in plain sight. Most Federal EEO complaints are, in the eyes of the law, without real merit.

For decades I have read summaries of Federal cases appealed to the Commission itself. A substantial number are allegations of bias that fail the required prima facie test required. Many of those are employees in trouble who are pushing back against a management that is unhappy with their performance or behavior. I have mediated many such cases.

The supervisors and managers taking actions against employees may be competent or incompetent, respected or disrespected. As humans, they have biases; however, that doesn’t appear to be the basis of their decision-making. Nevertheless, decent managers who confront and/or discipline workers should (and commonly do) realize such action may precipitate an allegation of discrimination.

When an EEO complaint is pursued in response to adverse personnel actions, it must be investigated and can proceed to a full-blown hearing: replete with discovery, agency attorneys, a court reporter, witness preparation, etc. The process can seem endless, overwhelming and isolating.

No good deed goes unpunished

Decent and dedicated management officials may find themselves bombarded by allegations of racism, sexism, ageism, etc. as a consequence for doing the right thing. While they are likely to prevail, what effect does such a complaint (or repeated complaints) have on someone in a leadership position?

From my own observations over many years, supervisors can wither under the scrutiny of counselors, investigators, representatives and judges. They have too often said to me, “It feels as if I’m guilty until proven innocent.”

While not technically accurate, there is good reason for such a perception. Senior leadership is asked to maintain a “hands-off” posture as an allegation of discrimination wends through the lengthy EEO process. Agency EEO officials must be vigilant in allowing the employee to be taken seriously. Attorneys worry about their agency’s image, witness preparation, the sufficiency of evidence, etc. as a case proceeds.

No one is assigned to care for the manager accused. Even when human resources and higher levels of management gave a green light to disciplinary action or a “performance improvement plan”, they are supposed to step to the sideline as the supervisor’s actions are investigated.

The hidden costs of exoneration

Perhaps because this is a very sensitive subject, little is discussed or understood about the effects of meritless complaints.

The costs associated with such cases are mostly under the surface. Management officials who prevail, commonly continue to work with the employee who has accused them of acting from bias. They know that any future actions regarding that same employee may result in an allegation of “reprisal”… even though they were exonerated. According to this same report, nearly half of complaints in 2014 alleged reprisal (Table 7).

Accordingly, supervisors too often walk on eggshells, harbor resentment, and exercise leadership while looking over their shoulders. This compromises their abilities and can affect all of those working under their leadership. Worse still, these managers harbor serious misgivings regarding the very idea of equal employment opportunity – a concept that should be important to anyone reading this article.

A few long-needed ideas

EEOC

I want an EEOC because I want workplace discrimination to be addressed and offenders sanctioned. I feel; however, as if the Commission is exercising some form of official silence by not drawing attention to how many Federal EEO complaints fail the legal standards they maintain.

The data I’ve referenced may not be damning, but it bears honest commentary from the EEOC itself. We should also know how data for the government compares to the private sector.

MSPB

On a different front, one of the missions carried out by the Merit Systems Protection Board is to conduct “merit systems studies”. Many of these studies have been excellent; however, I can’t recall the Board ever delving into the issues of time, money and morale I’m raising in this article.

With respect for real victims of bias and with honesty concerning those who use the system for less honorable reasons, the MSPB should examine the current landscape regarding Federal EEO complaints. Like others in my profession, I have read cases of individuals who have filed more than 100 EEO complaints. It is time for the Board to take a serious look at the average cost of an EEO complaint.

OPM

The Office of Personnel Management’s annual Viewpoint Survey should be asking Feds about equal employment opportunity and how it is perceived within the Federal workforce. Both employees and managers have attitudes, stories, resentments and wounds that might bear examination through the lens of a well-designed, broad-based survey.

For instance, I would like to know how many/often supervisors avoid taking needed remedial action due to fears of the EEO process and its aftermath. I would also know if the process intimidates employees from filing legitimate complaints.

Management Associations

I suggest that groups representing supervisors, managers and executives publish guides for their members/constituents. These guides would not only provide advice regarding the process but also advise them of how to care for their needs. Because management associations are not attached to the involved agency, they can address pragmatic issues like settlement, employee assistance program counseling, and the data I’ve cited above.

These groups should also be pressing the OPM, MSPB and EEOC for the kinds of things I’ve just articulated. The complaint process touches so many Federal supervisors and managers, it should be in the interest of such groups to lobby for a fully accounting and more complete picture of the process.

In summary

I know this article is limited in scope. It ignores grievance procedures which are more often used than EEO complaints as a means of protest. It barely acknowledges the racism, sexism, etc. that so many Feds have endured over the course of careers. It casts a more favorable light on supervisors and managers than many would prefer.

All that acknowledged, the EEO complaint process is lengthy and costly. Those investments may not be the most effective or efficient ones for today’s Federal workplace, given the data I’m citing.

While discrimination isn’t behind us and cases need to be prosecuted, some form of cost/benefit analysis needs to be employed by our government to ensure protections exist without wasting precious financial and human resources.