With all of the attention being paid to racism in our society, there is a lot of talk about systemic racism. I hear arguments that there is no such thing as systemic racism, that systemic racism is everywhere, and everything in between. Having spent decades involved in federal hiring programs, following are some thoughts on racism in hiring and other federal human resources practices.

Let’s begin with some definition of what this post is about. It is not about overt racism. We have all seen racists who own their racism and are happy to espouse every kind of negative view of people of races that are not their own. That kind of racism is obvious, deliberate, and has generally decreased in our society. This post is about racism that is far more subtle, and typically not deliberate. It is baked into the process, but the ingredient was not listed on the recipe as “1 cup of racism.” It was put there as something else, but the outcome disadvantages people based upon their race or other factors that are not really about merit.

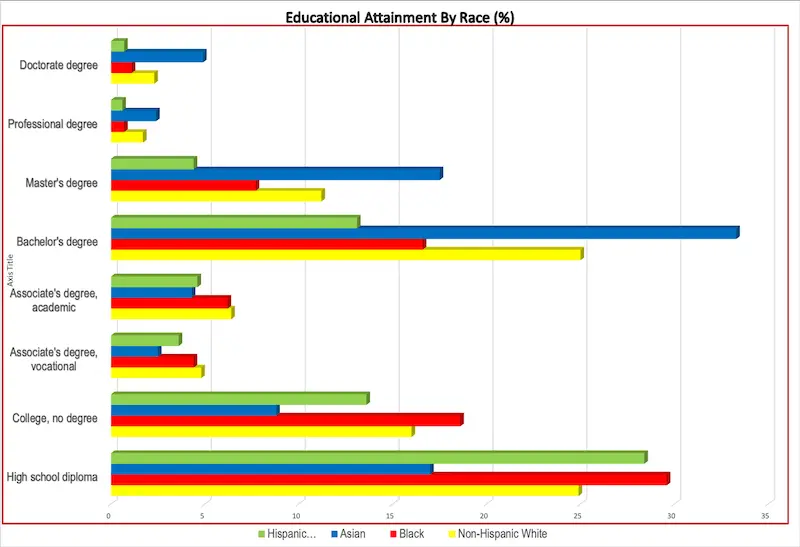

Qualifications requirements are one of the biggest sources of racism in hiring and promotion. They are described as being the core of merit-based hiring, but are they really? If an agency decides it wants to hire only people with Bachelor’s degrees, but the job does not require a degree and the agency has no proof that a degree leads to higher performance, the agency is discriminating against people who lack a particular credential that is not needed for the job. When we look at this chart of census data on education and race, it becomes apparent that a degree requirement that is not valid is likely to make more white and Asian people eligible for the job, and fewer Black and Hispanic people eligible. Was the intent to be racist? Probably not, but the intent does not erase the racially biased outcome of the decision.

There are other education-related practices that can result in racial disparities. For example, I have worked with many senior executives who like to recruit at particular schools (often their alma mater). Depending on the racial makeup of the school, the result can be racial disparity. Again, those are generally not cases where the person making the recruiting decision intends to discriminate based on race, but that is still the outcome.

Racism also exists in performance ratings. A good example is the experience of the Department of Defense in implementing the now-defunct National Security Personnel System (NSPS). The outcomes of rating and bonus payouts had a measurable bias against Black employees. When I was HR Director, the Defense Logistics Agency conducted its own study of ratings, bonuses and pay raises and had similar findings, even though the Agency was aware of the risks and had taken deliberate steps to reduce the likelihood of biased outcomes. In one of the pay pools I managed, managers discussed the ratings for two employees whose performance was poor — one Black and one white. Neither was someone we would rehire if they left. The recommendation was to give the white employee a satisfactory rating and the Black employee a marginal rating. When I challenged the recommendation, there was no good reason for the disparity. None of the participating managers intended to discriminate based on race, but that would have been the outcome if the ratings were allowed to stand. Ratings-based discrimination is often the result of the inherent biases that exist in performance rating processes. Studies have shown that people tend to be more impressed with people who remind them of themselves or have similar backgrounds to their own. When executives, managers and supervisors are disproportionately white, as they are in most agencies, the outcome is often that the employees who look like those leaders get the highest ratings and biggest bonuses. In the case of NSPS, DoD found that the biases were not caused by the NSPS law itself — they actually existed before in Quality Step Increases and performance bonuses. NSPS magnified the effects of the existing biases.

Another good example of racism is in discipline and adverse actions. Although agencies generally have little readily available data on the details of disciplinary and adverse actions, data that is available often shows a higher likelihood of Black employees being suspended for more days than white employees who commit similar offenses. Black employees are also more likely to be suspended when a white employee may be reprimanded for a similar offense. When reviewing individual actions, it is easy to justify them. The problem is when we compare similarly situated employees, the outcomes are often different based on race. The lack of data for disciplinary actions (particularly the reasons why people are disciplined) makes it difficult to recognize this type of discriminatory practice and correct it. Many years ago I presented data to a Commanding Officer that proved there was bias in disciplinary actions. His response? “Destroy the report and never talk about it again.”

Agencies often rely on years of experience for hiring and promotion decisions. Length of experience can be important, but only to the degree that those years give an applicant or employee adequate time to encounter the various types of work issues that a job involves. For example, it may take a year or two or more to go through a budget cycle, a performance rating cycle, a strategic planning process, and other key tasks. One year of experience is most likely not as good as three years of experience. But what happens when we compare three years vs. 10 years? Ten versus twenty? Is there really a difference in performance? As much as those of us with decades of experience would like to think it is true, those extra years of experience most likely do not result in better performance on the job. When we favor candidates who have many years of experience, the outcome may be that people who benefited from biases in hiring years ago continue to benefit by getting preferential treatment in the hiring or promotion processes. People who were the target of those biases likewise continue to be disadvantaged. A hiring manager who focuses on years of experience may not think that is a discriminatory practice, but the outcome may be just that.

The hiring process itself is cloaked in the language of merit, yet it is remarkably subjective. Managers get to decide what constitutes well-qualified. They decide who gets interviewed and who gets selected. Even getting to the interview can be highly subjective. A 2016 study cited in a 2017 Harvard Business School article showed that minority candidates who “whitened” their resumes got significantly more callbacks than those who did not. It said “In one study, the researchers created resumes for Black and Asian applicants and sent them out for 1,600 entry-level jobs posted on job search websites in 16 metropolitan sections of the United States. Some of the resumes included information that clearly pointed out the applicants’ minority status, while others were whitened, or scrubbed of racial clues. The researchers then created email accounts and phone numbers for the applicants and observed how many were invited for interviews. Employer callbacks for resumes that were whitened fared much better in the application pile than those that included ethnic information, even though the qualifications listed were identical. Twenty-five percent of black candidates received callbacks from their whitened resumes, while only 10 percent got calls when they left ethnic details intact. Among Asians, 21 percent got calls if they used whitened resumes, whereas only 11.5 percent heard back if they sent resumes with racial references.” Is it likely that hiring managers made those decisions because they were consciously being racists? No. Does that change the outcome? No — the outcome is a racially biased process that provides an advantage to white applicants.

When I raise these issues with some people, their first response is “I’m not racist!” Then they stop listening to descriptions of ways in which racism manifests itself in management decision-making. I believe the reality is that people who grow up white do not like to admit that we may have benefited from being white in American society. We want to think that everything we accomplished was 100% our work. We point to “merit” based processes and say “See — we earned it!” An old boss of mine used to say the most important thing was his version of the Golden Rule — “He who has the gold, rules.” In our society, the gold (and the decision-making power) is still mostly in the hands of white people. We should be far more open to the idea that what we think of as merit can be influenced by who we are, where we grew up, the people we work with, and many other factors that may or may not be objectively merit-based.

I believe systemic racism exists, and can be found in federal hiring, promotion, training and other Human Resources and management practices. Rather than proclaiming “I’m not racist!” we might find we make more progress if we say “I try not to be racist” and are open to hearing about ways in which our behavior has racial impacts. No one expects the world to change instantly, but it does not change at all if we refuse to admit that there are problems.