Opening your TSP statement and seeing your balance lower than you expected can feel like a punch to the gut. Remaining focused on the long run is hard when there’s volatility happening.

But it doesn’t need to always have to feel so terrible. You can be comfortable with how you’re doing by using some of the simple principles that we use as professional financial planners.

And the interesting thing is that you probably already know what to do, you just need to know how to do it. Knowing how to properly use your TSP is critical to the financial success of your retirement.

How many of you reduced your C fund investment last year? Increased your G fund? We talk to a lot of federal employees, and we see the biggest mistakes during times that markets are volatile, just like recently.

In this piece, we discuss some of best practices and along with mistakes to help you plan a better retirement.

Misunderstanding TSP Fund Risk Ratings

TSP Core Funds

| Fund | Investment Objective | Risk Level |

|---|---|---|

| G Fund | Ensure preservation of capital and generate returns above those of short-term U.S. Treasury securities | Low |

| F Fund | Match the performance of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index | Low-Medium |

| C Fund | Match the performance of the Standard and Poor’s 500 (S&P 500) Index | Medium |

| S Fund | Match the performance of the Dow Jones U.S. Completion Total Stock Market Index | Medium-High |

| I Fund | Match the performance of the MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australasia, Far East) Index | High |

When you visit the TSP website, they have a table that helps you compare the different TSP funds. It looks a bit different than above because you can only compare 3 at a time, but these risk ratings are taken directly from the TSP website. The TSP offers these risk ratings but offers no context.

Take, for instance, the G fund. While certainly a low volatility investment, it is ranked 1/5 on the risk table because of its principal protection features. Many people call this fund the safest TSP fund.

To opine, I prefer not to use the word “safe”. It’s misleading. It’s safe from volatility, but far from safe in helping you maintain your lifestyle over the years. Inflation is the silent portfolio killer.

With 3% annual inflation, you can expect to lose almost 30% of your purchasing power over ten years.

The net present value (NPV) is a part of the systems of economic equations used in helping determine how much money you’ll need to maintain your lifestyle, and what kind of growth you need to achieve that.

Let’s take the C fund next. It represents the S&P 500 and sits in the middle of the TSP’s risk table, labeled medium risk. How many of you think the S&P 500 is a medium risk investment? Not me!

It’s only when we look at all of them side by side that we can see that the TSP is comparing the funds to one another. So relative to the other funds, the C fund falls in the middle of their risk rating, because they have a total of 5 funds with 5 ratings.

Trying to Time the Markets

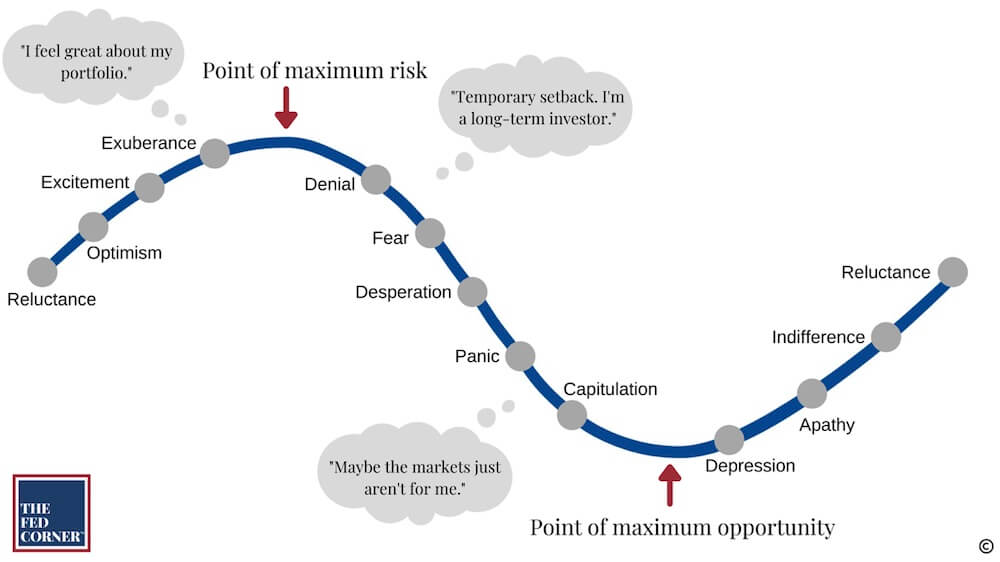

This is probably among the biggest mistakes that we’ll discuss. If you consider how emotionally challenging it can be seeing your portfolio drop significantly, imagine how those emotions can influence your decisions?

You have conflicting feelings about wanting to preserve what you have, but also grow your wealth for the future to support your family. You understand the need to outpace inflation, but the investments that allow you to do that give you anxiety when they become volatile and shave chunks out of your TSP balance.

If you think about 2022 or even 2020 when COVID first hit, masses of TSP participants moved to the G Fund to help preserve their wealth. How many of those people do you think successfully got back into the markets right before it took off again?

We spoke to feds who missed out on doubling their TSP because they got out near the bottom in 2020, and then couldn’t bring themselves to reinvest in investments that were falling from the sky.

As a result, they never got back in for the subsequent recovery. Their attempt at timing when it was right or wrong to be invested cost them dearly, and possibly to a degree from which they may never recover.

This can be catastrophic for your retirement because your wealth simply cannot regrow as fast once it has begun supporting you instead of just growing.

That’s not to say there aren’t times when going to the G fund isn’t appropriate, but if you’re making decisions based on fear rather than a plan, then you must consider whether you’ll be ready to make the move back correctly.

Below is my favorite graph, ever. Internalize it as best you can.

Investing Too Aggressively or Too Conservatively

It’s not infrequent that we hear federal employees refer to the TSP as being managed. Blackrock and State Street do not “manage” the TSP, they create the TSP funds for you to use on your own. The TSP funds are index funds, meaning they’re invested in sections of the stock (or bond) markets.

Neither the TSP nor sponsoring firms make changes to the core funds based on volatility in the markets. The only exception to this is if a holding is no longer inside an index; the fund would be adjusted to match the index once again.

The TSP core funds are designed to mimic its respective section of the market, and that’s what it does.

“The C and S funds have done really well for me”. This is another common thing we hear. Do not be persuaded by recency bias to remain in an investment that “has done well”. The markets are cyclical in nature, and by design those investments will experience a time where they won’t do well.

The C and S funds are stock indexes designed to participate in market growth. During periods of economic expansion—like the last decade—they do just that. They grow. They do this because the underlying sectors of the market in which they are invested are growing, the S&P 500 and Dow Jones Total Stock Market, respectively.

But this fundamental characteristic also means that volatility is tied at its hip. Growth and volatility are two peas in a pod. You [generally] cannot have one without the other.

Understanding that the TSP funds are simply index funds gives you perspective. And for what it’s worth: there’s nothing wrong with only being index funds.

In fact, we mostly use index funds for our clients too, but you need to understand how to use them.

As such, if technology companies are doing poorly, the C fund is not going to get rid of them for you. If you no longer want to own big technology companies, then you need to reconsider your use of the C fund.

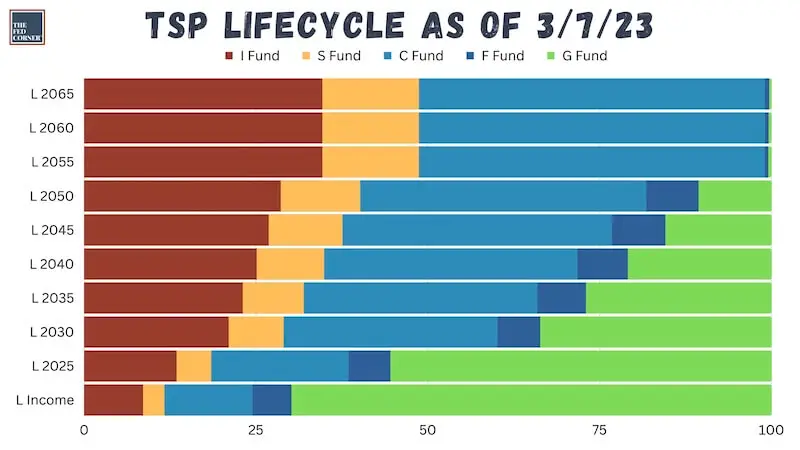

Even the Lifecycle funds are not managed, they are simply a combination of the five core funds that adjusts to being more conservative the closer you get to the target date you selected.

Not Fixing Drift

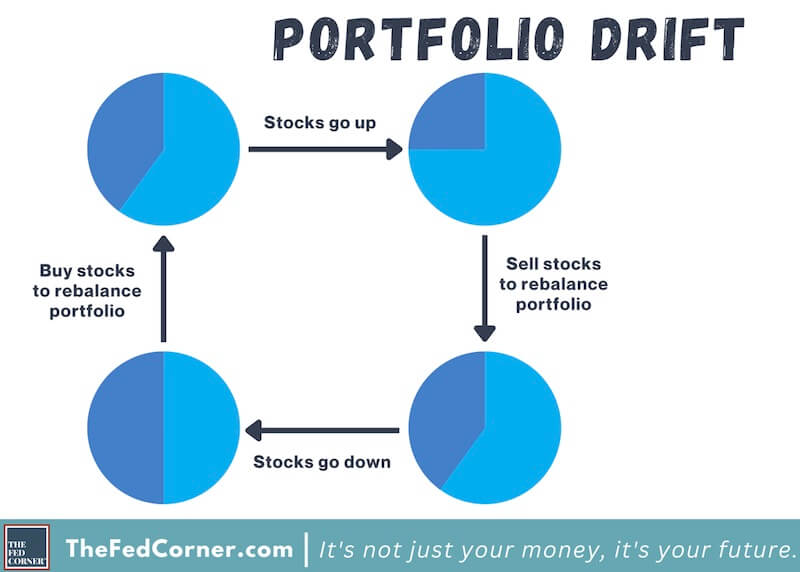

Being too aggressively or conservatively invested causes another major issue: portfolio drift.

The more volatile parts of your investments, like the C, S, and I fund (F too, to a degree), will become bigger or smaller portions of your overall wealth as the markets change in value.

If you maintain bigger values in your C, S, I fund, then you have increased the ratio of stocks in your portfolio. This increases the risk to your wealth, the volatility you’ll experience, and may create a deviation to your trajectory.

One way to help with this, especially if you don’t have experience in building a portfolio, is by using the Lifecycle funds.

As mentioned, it is not managed, but it is rebalanced. However, I’ve personally had mixed feelings about the L funds.

Lifecycle funds do not rebalance in its truest sense. It’s a time-based allocation. The further out you go, the more C, S, and I fund you can expect. The reverse is true as well.

But we’ve found that it tends to be a bit more conservative than we might have called for. The TSP builds a Lifecycle fund, for instance the L 2025 fund, the same way for everyone that choices that date, and the allocation is set assuming you’ll be accessing your TSP that date.

Sometimes your retirement date and the date on which you start making TSP distributions do not coincide. Often, this is intentional. We’ve had this be the case for many of our retirement clients.

Many federal retirees chose to do Roth conversions when they first retire and live off after-tax dollars instead. This would have made your Lifecyle date incorrect and your investment allocation possibly incorrect as well.

Additionally, should everyone retiring in 2025 deserve the same investment allocation? Your circumstance is different than your colleagues and your asset allocation should be different too.

Not Considering Asset Outside the TSP

One of the ways federal employees can strengthen their financial position is by diversifying the taxability of their investments. All your TSP is considered taxable if it’s in the Traditional TSP.

You may wish to consider the Roth TSP, but contributing to it is only available while working. Perhaps your tax bracket benefits more from Traditional while you’re working instead. As stated, your Tax Planning Window—that is, the time period in which Roth makes the most sense—doesn’t generally begin until you retire.

Prudent investors look to save outside the TSP as well. This can be done as easily as starting a savings account, individual or joint investment accounts, or a backdoor Roth IRA. Having some after-tax money growing for you can do wonders once you’re limited in where you can access cash.

When holding money outside of the TSP, you should consider those holdings within your overall asset allocation. This includes your savings accounts. We’ve spoken to families who had 25% or more of their total wealth sitting in bank savings accounts. It never occurred to them to view these dollars as a part of their portfolio allocation. This is imperative.

This also allows you to diversify your assets beyond the limited TSP core funds. The TSP tried to address the diversification issue by adding the mutual fund window, but we’re not yet a fan of it. It’s a bit clunky, restrictive, and the investment options have higher expense ratios than are reasonable.

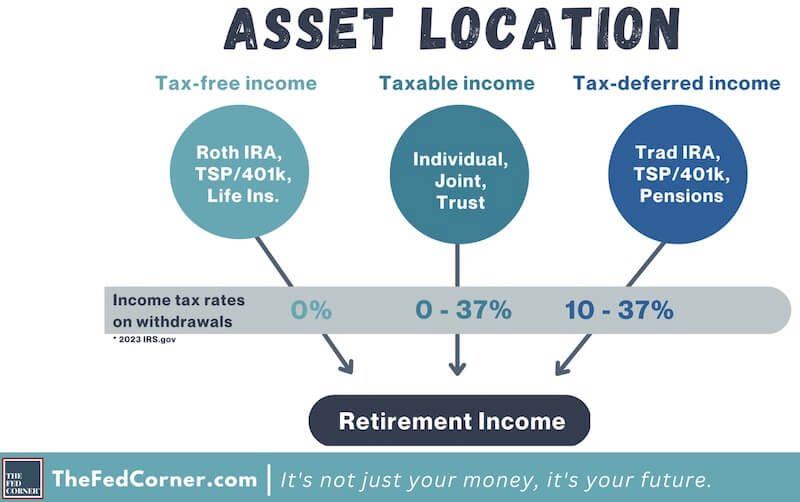

Incorrectly Using Asset Location

The next issue we often see federal employees make is not consider the tax-efficiency of their investments.

Most federal employees know the difference between Roth and Traditional retirement accounts, but very few understand how different investments have different tax efficiencies.

For example, mutual funds all have something called capital gains distributions. This means that even if you didn’t sell investments, you still have to pay capital gains taxes for that account.

I lost track of how many families came to work with us last year that had to pay taxes on investments in which they had losses. Taxes on losses. If that’s not demoralizing, I don’t know what is.

This was due to their use of certain investments in the wrong manner. The same is true for your retirement accounts.

Retirement accounts are tax-deferred, meaning they’re tax favorable. It stands to reason that you should be holding your most tax-inefficient investments like high yield bonds, mutual funds, and others inside those accounts.

The same is true for your growth assets. Keeping the most aggressive growth inside your Roth accounts makes a great deal of sense. Growth on investments means taxes, either capital gains or income tax, so why not get the most growth inside the tax-free account?

The following graphic illustrates various investments and their tax-efficiency. I recommend you save this image or take a screenshot to have it handy for use when building your portfolio.

Take the time to familiarize yourself with the concepts above, and truly internalize the messages presented. It could mean the difference between a successful and failed retirement plan. If you want to learn more about planning concepts like these, sign up for the Fed Corner’s free newsletter.