The Department of Defense recently released new rules for reduction in force (RIF). Required by language in the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the new rules are the biggest shakeup in RIF in decades.

The new rules change the order of RIF retention factors to make performance ratings the primary factor in determining who to let go in a RIF. Anyone who has conducted a RIF in the past understands the significance of the change. “Seismic shift” is a good way to describe it.

Changing the retention order to make performance the most critical will have many implications. Whether they are good or bad will depend on your perspective.

Some folks will see these changes as a long-overdue recognition that RIF rules often lead to the removal of high performers at the expense of others. Other folks will see the changes as putting more emphasis on a performance management process that can be charitably described as “flawed.” Others will see the lessening of the benefits of veteran preference as a problem (or a benefit). To get to the rules and what they mean, let’s start with the language in the NDAA:

Sec. 1101. Procedures for reduction in force of Department of Defense civilian personnel

(a) Procedures. Section 1597 of title 10, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following new subsection:

(f) Reductions based primarily on performance

The Secretary of Defense shall establish procedures to provide that, in implementing any reduction in force for civilian positions in the Department of Defense in the competitive service or the excepted service, the determination of which employees shall be separated from employment in the Department shall be made primarily on the basis of performance, as determined under any applicable performance management system.

(b) Sense of Congress. It is the sense of Congress that the Secretary of Defense should proceed with the collaborative work with employee representatives on the New Beginnings performance management and workforce incentive system authorized under section 1113 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2010 (Public Law 111–84; 5 U.S.C. 9902 note) and begin implementation of the new system at the earliest possible date.

The changes DoD made to its RIF processes are being driven by the law. The Congress passed the NDAA and President Obama signed it. The implementing memorandum also makes a key point that should not be overlooked. Heads of DoD components are directed to use every reasonably available means of reducing the number of people who might be affected by a RIF, including buyouts, early retirement, hiring freezes, retraining, and other means. That is a clear signal that DoD still views RIF as tool to be used only after less disruptive means of reducing the workforce have been tried.

Government-wide RIF Rules vs. the New DoD Rules

Under the government-wide RIF rules, performance has an indirect effect on RIF retention and comes after tenure group (career/career conditional/non-permanent), veteran preference status (30% disabled/other preference eligibles/non-veteran and veterans without preference), and service computation date (SCD). Performance comes into play by adding up to 20 years of service credit for performance ratings. Here is how it works:

Subgroup

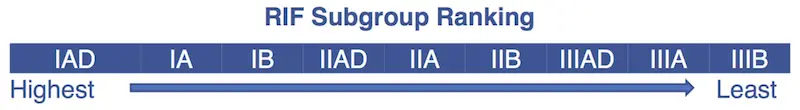

Employees are assigned to a subgroup based on the the factors listed above. A “subgroup” is the combination of your tenure group (career (I) , career–conditional (II), or non-permanent (III)) and your veteran preference (AD -30% disabled veteran, A-other preference eligibles, or B-non preference eligible). If you are career-conditional or serving under certain types of probationary periods, you are in tenure group II. Career employees who are not serving probationary periods are in tenure group I. Employees who are serving time-limited appointments are generally in tenure group III. Those without veteran preference for RIF (even some veterans), have veteran preference code ‘B’. Employees with veteran preference for RIF (including surviving spouse preference), who are not a 30% disabled veterans, are in code ‘A’. Employees with veteran preference for RIF and a 30% or more disability are in Subgroup ‘AD’. When we combine the two factors, we get the Subgroup. A career employee without veteran preference, for example, is in subgroup IB. Most placement rights depend on Subgroup. The Subgroups are listed below:

Service Computation Date (SCD)

Your Service Computation Date is based on the number of years of service you have. You get credit for time in civil service jobs and in the military. If you are retired military, you usually don’t get credit for all the time you were in service. You will get credit for time you spent in combat zones, on campaigns or expeditions, and similar assignments. There are a number of circumstances that affect credit for military service. The Code of Federal Regulations provides more specifics at §351.503.

Performance Ratings

SCD for RIF is adjusted based on performance ratings. Employees get credit for their last three annual ratings, as long as they are not more than four years old on the day RIF notices are handed out. The following amounts of credit are generally given for ratings: 20 Years for Level 5, 16 Years for Level 4, 12 Years for Level 3. Level 1 and 2 ratings (marginal/unsatisfactory) do not add anything to service credit. Because virtually everyone gets a satisfactory or higher rating, the practical impact of an outstanding performance rating is only 8 years or less.

New DoD Rules

The new DoD rules completely change the process. Rating of record becomes the most critical factor, followed by tenure group, average performance rating, and veteran preference. A DoD Service Computation Date for RIF becomes the tie-breaker. In addition, the “bump” and “retreat” rules are changed to eliminate the “retreat” process. DoD’s policy guidance includes much more detail and I encourage anyone interested in learning more to to take a look at it. Here is a brief explanation of the new rules.

Rating of Record

This is the average of the employee’s two most recent performance ratings within the last 4 years. If the employee has only 1 rating, that one is used. DoD’s rules prohibit components from issuing ratings solely for use in a RIF, and require a cutoff for new ratings at least 60 days before RIF notices are issued.

Tenure Group

These are mostly like they are everywhere else

Average Score

This is where it gets complicated. The average score is the “average of the average scores drawn from the two most recent performance appraisals received by the employee, except when the performance appraisal reflects a score of “unacceptable” rating of record.” The Average Score is not the same as the Rating of Record. It is looking at the average score in the rating process (e.g., 4.7 on a 5-point scale) versus the overall rating (Outstanding, Satisfactory, etc.).

Veteran Preference

DoD uses the same three categories as the rest of the government.

DOD SCD-RIF

The DoD service computation date for RIF does not include extra service credit for performance ratings. The ratings are used prior to getting to the point of considering SCD, so there was no point in adding them in again.

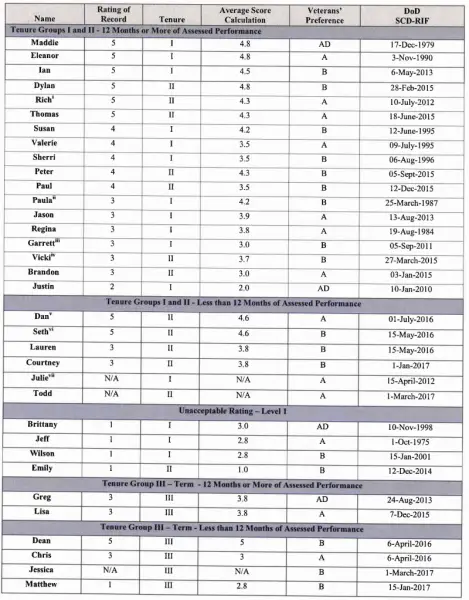

Below is a sample retention register that was included in the DoD guidance:

As you can see, the move to performance ratings makes a dramatic difference in the retention standings. Dylan, a career-conditional employee without veteran preference, is ranked above 8 career employees, including 4 veterans. He is also ranked above 2 other career-conditional employees who have veteran preference. Dylan’s ranking is based on his outstanding performance rating. To quote another Dylan – “The Times, They Are A-Changin’.”

What Does it Mean?

I have conducted a number of RIFs, including one that abolished 700 jobs. After all the bumping and retreating was done, that one affected 1500 employees. These new rules make the RIF process more complicated and reduce or eliminate the idea of “last in, first out.”

If I had complete confidence in the performance rating process, I would say the change is very good. It will allow the Department of Defense to prioritize keeping its best performers during a RIF. That is a good thing.

On the other hand, my concerns about performance ratings make me want to see much more focus on building a performance appraisal process that is manageable, unbiased, and likely to lead to better performance.

There is likely to be some debate over the lessening of veteran preference for RIF. As written, DoD’s rules do make veteran preference the deciding factor when have the same Rating of Record, Tenure Group, and Average Score, but that is a big change. For employees who are relatively new and/or whose performance is rated as outstanding, or employees with veteran preference and a less than outstanding rating, the new rules are a very big deal. This is the type of change that does not happen often, and that could become part of a larger government-wide civil service reform effort.